What was agreed on climate change at COP30 in Brazil?

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesCountries have reached a new deal to tackle climate change at the annual UN meeting in Belém, Brazil.

But many countries were unhappy with the outcome, with no new measures on fossil fuels or deforestation.

What is COP30 and what does it stand for?

COP30 was the 30th annual UN climate meeting.

COP stands for "Conference of the Parties". "Parties" refers to the nearly 200 countries that have signed up to the original UN climate agreement of 1992.

When was COP30?

COP30 was due to run from Monday 10 November to Friday 21 November.

But the talks overran into Saturday 22 November.

World leaders gathered on Thursday 6 and Friday 7 November, before the conference began.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhy was COP30 held in Brazil?

The host nation is chosen by participating countries after a nomination from the host region.

The conference was held in Brazil for the first time.

The choice of Belém, on the edge of the Amazon rainforest, caused significant challenges.

Some delegations struggled to book affordable accommodation, leading to concerns that poorer nations could be priced out.

The decision to clear a section of Amazon rainforest to build a road for the summit also proved controversial.

Brazil also continued to grant new licences for oil and gas which, alongside coal, are fossil fuels, the main cause of global warming.

Who was at COP30 – and who wasn't?

UK Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer, French President Emmanuel Macron, German Chancellor Friedrich Merz and Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva were among those to attend the leaders' summit.

UN secretary general António Guterres and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen were also there.

The Prince of Wales, attending on behalf of King Charles, gave a speech calling for countries to come together to tackle the "fast-approaching" threats of future climate change.

PA

PABut many leaders were absent, including China's President Xi Jinping and US President Donald Trump. China and the US are the two biggest emitters of planet-warming gases.

Delegations from more than 190 countries, including a large number from China, attended the talks, however.

The US government did not send any national officials, although some local and state leaders did attend.

Politicians and diplomats were joined by scientists, campaigners and journalists.

Previous summits have been criticised for the large number of attendees who are connected to the coal, oil and gas industries. Campaigners argue this shows the ongoing influence of fossil fuel advocates.

Why was COP30 important?

COP30 took place at a time when global climate targets were under significant strain.

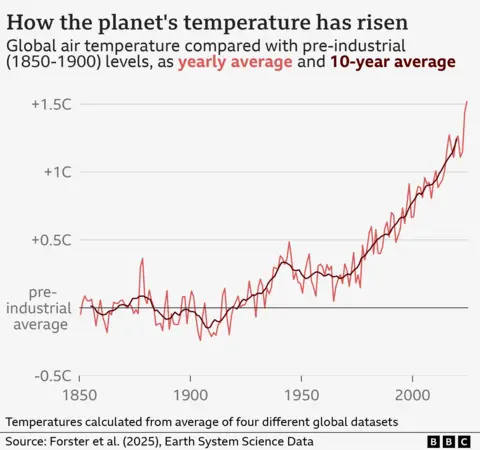

In Paris in 2015, nearly 200 countries agreed to try to limit global temperature rises to 1.5C above "pre-industrial" levels and to keep them "well below" 2C.

There is very strong scientific evidence that the impacts of climate change - from extreme heat to sea-level rise - would be far greater at 2C than at 1.5C.

But while the use of renewable energy - particularly solar power - is growing rapidly, countries' climate plans have fallen short of what the 1.5C goal requires.

Ahead of COP30, countries were supposed to have submitted updated plans detailing how they would cut their emissions of planet-warming gases. However, only a third had done so by the end of October.

UN secretary general António Guterres warned that "overshooting" 1.5C is inevitable, given how close the target is and how high emissions remain.

But he said he hoped temperatures could still be brought back down to the target by the end of the century.

Reuters

ReutersWhat was agreed at COP30?

Brazil hoped to agree steps to deliver commitments made at previous COPs.

Fossil fuels

At COP28, in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in 2023, countries agreed for the first time about the need to "transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems".

Brazil wanted the talks to secure clearer steps for how countries would achieve this.

The idea of such a "roadmap" had been backed by dozens of countries, including the UK, but was strongly opposed by others, including those reliant on fossil fuels.

In the end, the deal mentioned that existing UAE agreement - but did not strengthen the language around moving away from fossil fuels.

Brazil announced its own plan to launch a fossil fuel "roadmap" which countries could sign up to - but it sits outside the main deal.

Money

At COP29, richer countries committed to give developing nations at least $300bn (about £229bn) a year by 2035 to help them tackle climate change. But that is far less than poorer countries say they need.

That agreement also included an aspiration to raise this to $1.3tn from public and private sources.

Ahead of COP30, Brazil published a "roadmap" detailing how the $1.3tn goal could be achieved.

The COP30 deal called for a trebling of money to help the worst affected nations to adapt to the impacts of climate change, by 2035.

But it's not clear how much will come from public versus private sources. And richer nations have consistently undelivered on their cash promises.

Nature

At the leaders' summit ahead of COP30, Brazil launched the "Tropical Forests Forever Facility" - a fund which hopes to raise $125bn (£96bn) from loans and investments.

The aim is to try to prevent the loss of tropical forests by rewarding countries who keep their forests standing.

But the UK said it would not be committing public money - though could do so in the future and would encourage the private sector to invest.

Brazil announced plans to launch a roadmap outlining steps to meet the pledge to halt and reverse deforestation, which was made in COP26 in Glasgow in 2021.

But, like fossil fuels, this deforestation roadmap did not make it into the final deal.

Reuters

ReutersWill COP30 make any difference?

UN climate talks rely on consensus - all countries present have to agree in order to pass a deal.

That can be challenging. Different nations have competing priorities, based for example on their dependence on fossil fuels, economic position or vulnerability to climate change.

The backdrop for the talks this year was dominated by the fracturing consensus on tackling climate change, not least from the Trump administration.

The US President has pledged to boost oil and gas drilling, withdraw from the Paris climate agreement and roll back green initiatives put in place by his predecessors.

Some observers, such as campaigner Greta Thunberg, have accused previous COPs of "greenwashing" - letting countries and businesses promote their climate credentials without actually making the changes needed.

Significant global agreements have been reached at previous COP sessions, allowing greater progress than national measures on their own.

Despite the difficulties of delivering the 1.5C warming limit, the commitment - agreed at COP21 in Paris - has driven "near-universal climate action", according to the UN.

This has helped bring down the level of anticipated warming - even though the world is still not acting at the pace needed to achieve the Paris goals.

But the view from many scientists and observers is that the agreements made at COP30 are unlikely to shift the dial much on climate change.

Sign up for our Future Earth newsletter to keep up with the latest climate and environment stories with the BBC's Justin Rowlatt. Outside the UK? Sign up to our international newsletter here.