'A wicked wife': The truth about Tudor England's 'most hated woman'

Alamy

AlamyThe 16th-Century aristocrat Jane Boleyn faced explosive accusations: she was blamed for a shocking betrayal of her husband, as well as two of Henry VIII's wives, her sister-in-law Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard. Was she a "sex-mad" spy, guilty-as-charged – or a convenient scapegoat for a tyrant's brutality? A new historical thriller by Philippa Gregory, Boleyn Traitor, explores her story.

In the court of the mercurial King Henry VIII, nobody was safe, and the confidants of queens and courtiers could quickly switch allegiance. Lady-in-waiting Jane Boleyn, who served five queens − including her sister-in-law Anne Boleyn and Anne's cousin Catherine Howard, both executed by King Henry VIII – has long been painted as one such turncoat, surviving under suspicious circumstances when all around her were sent to the block. Blamed for betraying them, arguably she became, writes author Tracy Borman, chief historian at Historic Royal Palaces, "the most hated woman in Tudor England".

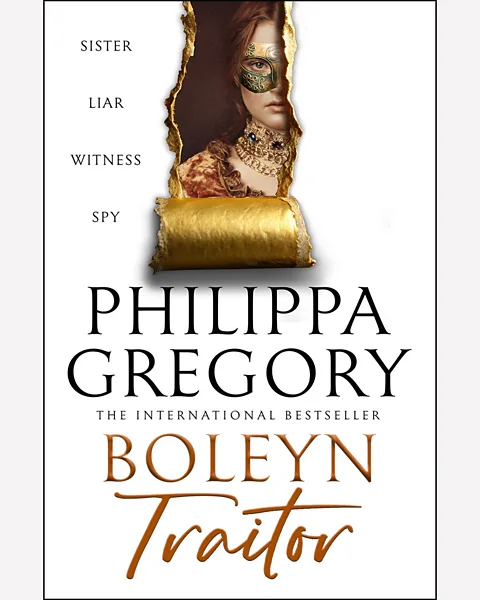

HarperCollins

HarperCollinsThis notorious figure, who acquired the title Viscountess Rochford in 1529, is the subject of a new book, Boleyn Traitor, a historical thriller written by Philippa Gregory CBE, whose hit novel, The Other Boleyn Girl, inspired the 2008 film of the same name starring Natalie Portman and Scarlett Johansson. "Jane has been on [my] mind since I wrote The Other Boleyn Girl, and since then, there have been some great new biographies of her," Gregory tells the BBC. "For any lover of Tudor history, she's this enigma, right in the middle of the story, who against all the odds, survives the fall of the Boleyns."

Jane Boleyn, born Jane Parker in around 1505, was the daughter of a baron who served as a gentleman usher to Henry VIII and translated Italian renaissance texts for the court. She arrived at court aged just 11, appointed as maid-of-honour to Henry VIII's first wife, Katherine of Aragon. It was there that she met the Boleyn family. Aged around 20, she made an advantageous marriage to George Boleyn, whose sister Anne – in an unanticipated twist – would be queen within a decade.

Little trace of Jane remains in the archives, leaving a blank page for storytellers to fill with sensational tales. There is also no confirmed painting of her, though there are drawings by Hans Holbein which are thought to be of her, and some have pointed to An Unknown Woman in Tudor Dress and A Lady Unknown, also by Holbein, as offering possible likenesses.

Alamy

AlamyMost images were doubtless destroyed in 1541 when Jane was charged with treason and denounced by the legislator, Lord Chancellor Audley, as a "bawd" (brothel madam) for helping Henry VIII's fifth wife, Catherine Howard − a teenager married to an infirm and impotent king − to conduct an affair with the handsome courtier Thomas Culpeper. All three paid with their lives. Culpeper's head rolled first, with Catherine and Jane brought to the scaffold two months later, executed at the Tower of London in quick succession on the morning of 13 February 1542.

The evidence suggests that Jane, in service to the queen, was indeed party to the secret liaisons. But, for Gregory, Jane is hated less because of her actions than the "outdated answers" used to explain them. "Her reputation changes over the years as each cohort of new historians have their own view on women, and they reflect that in Jane," she tells the BBC. "In the earliest documents, Jane is shown as nothing worse than a not very efficient duenna [lady's companion]," she says. But, later, the moralistic Victorians see her involvement in the affair "as evidence that she is a 'bad' woman".

Mired in scandal

Jane's presence during the couple's trysts, conventional at the time, is seen through a different lens. "Historians after Freud suggest she's a voyeur, sex-mad, driven by perverse desires, and after that, she's reported as simply mad," says Gregory. "I don't think Jane was driven by lust or any other sin," she adds. "I think she was just a normal woman in extraordinary circumstances, trying to survive and prosper."

Alamy

AlamyThis was not the first time that Jane had been implicated in the betrayal and downfall of a monarch. In 1536, the court was mired in scandal when Anne Boleyn was accused of committing adultery with four courtiers. To ensure there was no road back for Anne, a trumped-up accusation of incest with her own brother George was added to the charge. This accusation was allegedly disclosed to the King by none other than George's wife, Jane, who, it was suggested, envied the siblings' closeness. Speculation that the couple were unhappy, by historians from the Elizabethan period onwards, has also conveniently supplied Jane with a motive for treachery.

The scandal claimed the heads of both George and Anne – a neat solution for the king, whose attentions had moved to Jane Seymour, whom he hoped might succeed where Anne had failed, and deliver a much-needed male heir.

More like this:

• How history got Henry VIII wrong

"The fact that Jane was the only member of the Boleyn family to stay in post after the execution of her husband and sister-in-law has led to widespread assumptions that she had a hand in their downfall. In fact, there is precious little evidence for this," says Tracy Borman, who has written widely on the Tudors, including a new book, The Stolen Crown. "Jane was one of a number of Anne's household who were forced to provide evidence, and there is no indication that hers was damning," she tells the BBC.

Alamy

Alamy"In fact, we know that she petitioned Henry VIII on her husband's behalf." Asked if Jane deserves our condemnation, she replies, "Not at all," noting a move among contemporary historians "to reappraise certain key − and mostly female − figures from the Tudor era… and to strip away centuries of misogyny and misinterpretation".

To recognise the scapegoating of Jane is not to say that she lacked agency. "I think it's very easy to underestimate Jane's ambition, partly because we're conditioned to think of ambition as a bad thing for women," says Gregory. It was this ambition that drew her back to the dangerous court after her banishment in 1534 for conspiring with Anne Boleyn to remove one of the king's mistresses, and again in 1536, shortly after her husband's execution – a decision that cemented her icy reputation.

Alamy

AlamyPerhaps Jane's greatest mistake, compelled by her love of court life, was to place her trust in its most powerful patriarchs. Both Thomas Howard (when she was too young to know better) and, later, Thomas Cromwell (who, when she was widowed and financially insecure, most likely facilitated her reintroduction to court) offered her their patronage in the hope that Jane would spill information on the royal households she served – a circumstance which has led to her being branded a spy. But the balance of power was clear when they each dropped her as soon as the court's shifting politics made the alliance unwise.

"The more I dug through the records, many ignored for centuries, the more obvious it was that Jane Boleyn's story was not only just as gripping as those of the queens she had served but that she had been thoroughly maligned," writes Julia Fox in her 2007 biography, Jane Boleyn: The Infamous Lady Rochford, which takes its title from the 19th-Century historian Charles Coote's scathing description of Jane.

Her detractors, writes Fox, were "happy to find a scapegoat to exonerate the king from the heinous charge of callously killing his innocent wife", claiming that "it was her evidence that had fooled Henry and destroyed Anne and George". Yet, for Fox, such allegations make little sense, as Jane stood to lose so much. "She had no need to slander her husband, especially when the financial implications of such a move would be ruinous," she writes.

Alamy

AlamyLong after Jane's death, when Elizabeth I sought to strengthen her rule's legitimacy by rehabilitating the reputation of her mother Anne Boleyn, it again became useful to vilify Jane. George Wyatt's biography, The Life of the Virtuous Christian and Renowned Queen Anne Boleigne, for example, published in 1817, but penned in the late 1500s, describes Jane as a "wicked wife, accuser of her own husband, even to the seeking of his own blood". Dramatists, through the ages, have tended to follow suit. Anne Boleyn: A Dramatic Poem (1826) by Henry Hart Milman, for example, refers to "the unprincipled and unnatural character of the Countess of Rochford", while, more recently, the BBC series Wolf Hall, based on the novels of Hilary Mantel, portrays her as a jealous wife spreading malicious gossip.

Though Jane's life was cut short in her mid-30s, Gregory presents her story as one of survival, having maintained a career at one of history's most fickle courts, working under one of its greatest tyrants. Far from deliberately betraying Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard, we get a sense of the sacrifices she made to serve them, helping to rid them of rivals and, against her better judgement, to experience genuine love. All three women now lie in a chapel within the Tower of London.

Alamy

AlamyBoleyn Traitor invites us to condemn not Jane, but the power structure surrounding her. "This is a novel about tyranny," Gregory says, and "a reign that concentrated power on one man, and very few had the courage to stand against him".

Gregory's telling of Jane's story is not a pleasing moral tale where a villainess meets her end, but a warning about recognising danger too late. "Jane's awakening in the novel is when she understands that tyranny must be opposed when you first see it," says Gregory.

Boleyn Traitor by Philippa Gregory is published by HarperCollins.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.